Rethinking MTTR

Is elevating DORA (& friends) metrics to business indicators a trap?

I've spent the last few years working with various metrics, including DORA, and particularly with MTTR. Here stands a first layer of confusion as it can be meant as Mean Time To Recovery/Restore/Resolve, and sometimes even Respond, but we'll stick to the widely accepted one: Recovery, meaning: impacted users are, in one way or another, interacting with the system again successfully.

While these metrics are usually adopted as business KPIs, I believe we need to reconsider their role and keep them as operational metrics only.

Here's my thought.

A Statistical Significance Problem

MTTR's statistical significance is remarkably low. When we look at incident data, we often see a non-normal distribution of recovery times. Some incidents take minutes to resolve, while others might take days, independently of their impact and severity. Moreover, most companies, especially small and medium-sized businesses, don't experience enough incidents to achieve statistical significance in their measurements. And if they do have a high volume of incidents, that itself should be their primary concern rather than optimizing their MTTR.

Also, not all incidents are created equal. Usually, MTTR treats all incidents the same way: a one-day minor incident affecting a single user carries the same weight as a one-hour major outage affecting millions of users. This leads to misleading metrics that don't reflect the real impact on our services.

This wide variance and apple-to-oranges comparison makes it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions from the mean value alone.

The Real-World Disconnection

As mentioned, MTTR isn’t usually implemented in companies considering incident severity and impact. A quick recovery from a minor issue improves your MTTR more than a well-handled major incident that naturally takes longer to resolve. This creates perverse incentives where teams might be tempted to categorize incidents as multiple smaller issues rather than one larger one.

Also, the quality of the remediation isn’t taken into consideration. Recovery, intended as Mitigation so that users journey are completed again on the systems, is just part of the equation. It could be considered acceptable to mitigate the availability sacrificing latency, but is it for days? Or weeks? The benefit of proper recovery, or better, the fixing the root cause is not included in the MTTR.

The Actionability Problem

Here's a crucial question: If your MTTR goes up, what specific actions should you take? There's no clear answer beyond "investigate the context". Similarly, if MTTR goes down, does it necessarily mean your service is more reliable? Not really. This lack of clear actionability makes it problematic as a target metric.

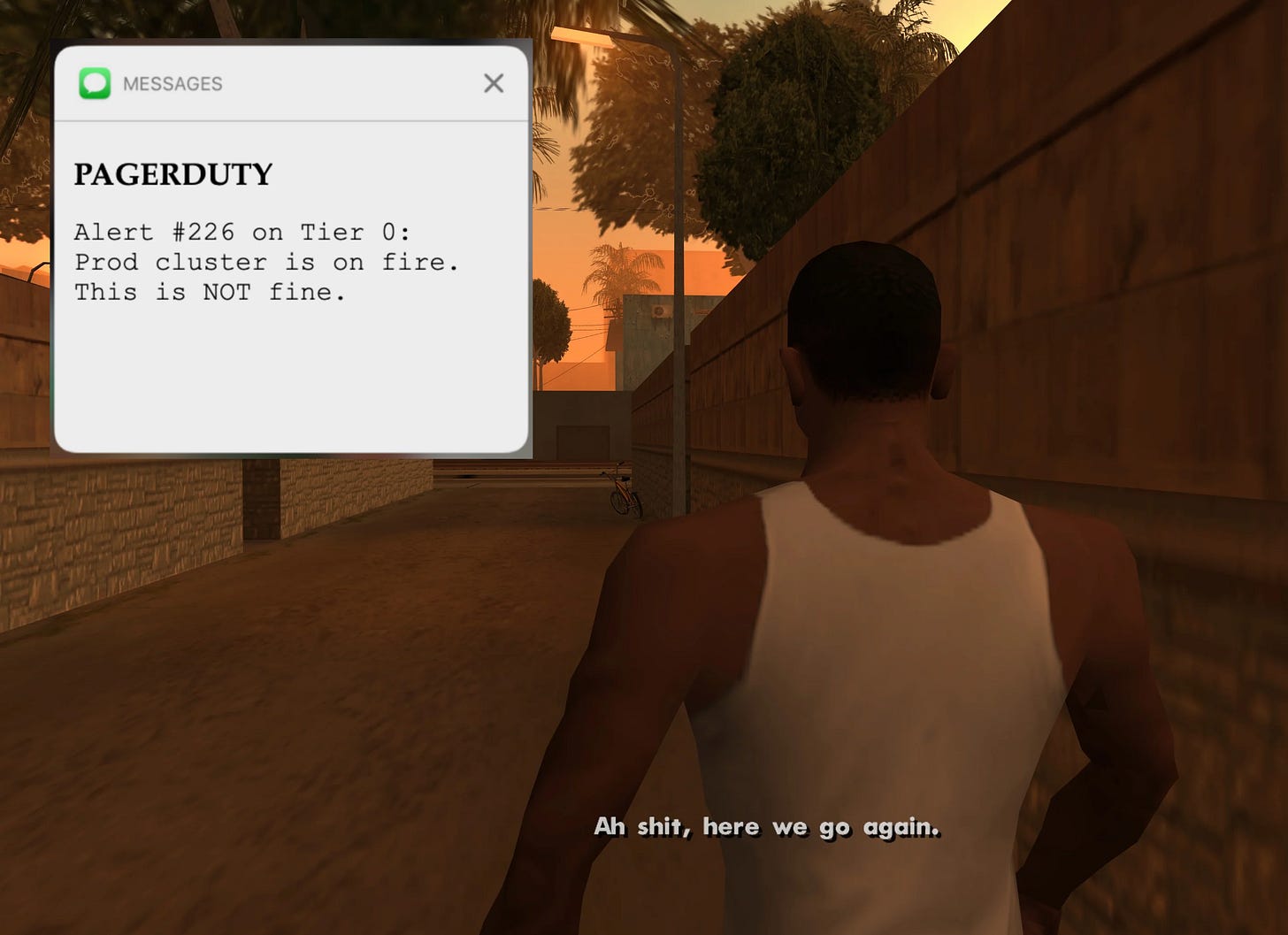

Consider a scenario where your team has gotten remarkably good at applying quick fixes to recurring issues. Your MTTR looks stellar on paper – dropping from hours to minutes – but you're masking a more insidious problem: architectural flaws that keep causing the same failures. You're optimizing for speed of repair rather than addressing root causes, essentially rewarding firefighting over fire prevention.

The metric can also create perverse incentives. Teams might rush through fixes to maintain a low MTTR, potentially introducing new vulnerabilities or technical debt in the process. Or worse, they might start classifying incidents differently. Breaking up what should be one large incident into several smaller ones, or prematurely marking issues as resolved only to see them resurface hours later. The metric becomes a game to be played rather than a true measure of service reliability.

Even more troubling is how MTTR obscures the customer impact dimension. A five-minute outage affecting your entire user base could be far more damaging than a two-hour incident affecting a small subset of users, yet MTTR treats them identically. This disconnect between metric and business value makes it dangerous to use MTTR as a primary indicator of operational excellence or team performance.

The Google Paradox

Allow me to use this silly but simple paradox: Google, who invented the SRE concept, has been working on incident management for years. If MTTR were a consistently improvable metric (and this is what business usually looks for), Google's MTTR should be near zero by now. But it isn't, because new features, systems, and complexity constantly introduce new types of incidents, as is normal, so why put pressure on the entire engineering department for something that is non-gaussian distributed, non-continuously improvable by nature, and that is not actionable?

If we still want to keep these metrics, just leave them as just another indicator for the authorized personnel.

The Business Metrics Trap (and a proposal)

I won't go deep into this large and widely discussed topic around why using DORA metrics as business indicators on the quality of Engineering creates problematic incentives, but it's clear that when promotions or OKRs depend, for example, on MTTR, teams might: split larger incidents into smaller ones, rush recoveries without proper root cause analysis, manipulate incident definitions to improve metrics, and so on.

Instead of fixating on MTTR, we should focus on:

Service Level Objectives (SLOs) that directly measure User Experience and especially User Journeys. Spoiler: It's more difficult, requires more time and shared effort beyond Engineering to negotiate what's important.

Reliability metrics that matter to specific services, prioritized by the Pareto principle.

Service availability measurements and engineers’ perceived stability (more on this soon).

These metrics provide more actionable insights and better align with business goals.

Measuring Success in a different way

We can better measure reliability improvements using different approaches, such as frameworks that are already adopted by business like the Kirkpatrick model.

We could, for example, every quarter or semester:

Survey incident managers and on-call people about perceived reliability trends.

Gather detailed feedback about specific services and pain points.

Convert qualitative feedback into quantifiable metrics to track trends across categories that align with our systems and needs.

Track these metrics over time to demonstrate improvements and take targeted actions in context.

To conclude, while MTTR and other DORA metrics (may) have their merits as operational indicators, their elevation to business KPIs deserves reconsideration. The non-normal distribution of recovery times, the lack of severity weighting, and the potential for creating misaligned incentives suggest we need a more nuanced approach.

Instead, organizations would benefit from focusing on comprehensive SLOs that genuinely reflect user journeys, developing context-specific reliability metrics, and implementing qualitative feedback systems like quarterly surveys of incident responders.

By shifting our focus from abstract, potentially gameable metrics to meaningful measurements that capture real service reliability and user impact, we can foster genuine improvements in our systems. The path forward lies in understanding that reliability isn't just about recovery speed, it's about building resilient systems, making informed decisions based on service-specific needs, and maintaining a holistic view of system health that considers both quantitative and qualitative indicators.

Resources: